Food labelling: What’s at the back, needs to be upfront

Certify your brand from our veteran food experts and win the trust of your consumer.

Natasha is a single mother to a 5-year-old. She leads a busy life juggling her work, home, ageing parents and a growing child and therefore looks for simpler and convenient solutions in most of her aspects of life. She prefers buying things from large format internet retailers.

Off late, she has realized that her 5 yo is distracted from his homework. He doesn’t want to play with his friends. She gives him milk, but he hates drinking it. She tries to make him eat vegetables, but he doesn’t eat that either.

How can she make him eat food which he enjoys and contains all the necessary nutrients? She started making an effort to read labels of biscuits and snacks which he enjoys. She wants him to eat products are ‘good for him’. But even as she buys the packaged foods, she cannot decipher the nutrition labels.

Complex words like sodium, saturated fats and serving size vis-à-vis recommended dietary allowance were difficult concepts to understand for her. She had a tough time calculating how much sugar and `fat does a child get on eating a bowl of cereal?

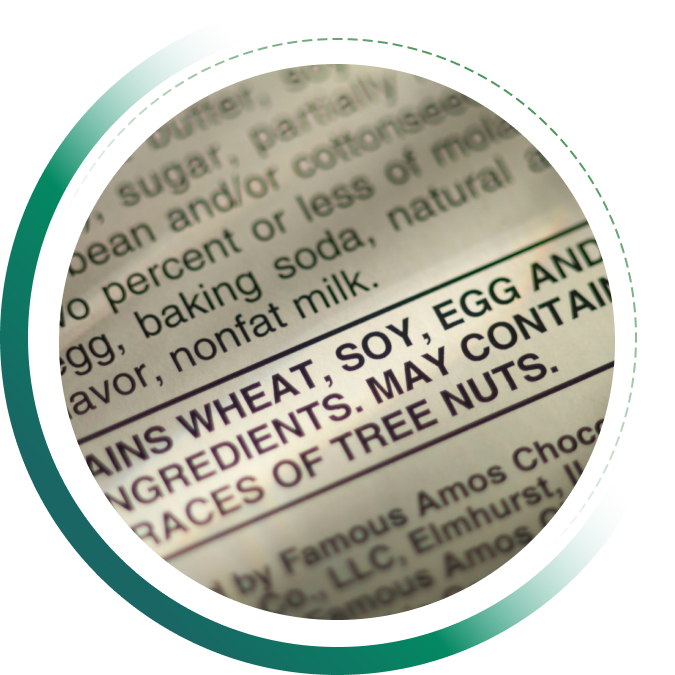

She realised that critical information was written on the back of the pack in cryptic language and beyond the comprehension of a regular consumer.

Not only does one need a n pair of magnifying glasses to read the super tiny text, but also grasp the complex terminologies. While the front of pack was full of colourful imagery, the crucial information was tucked away at the back.